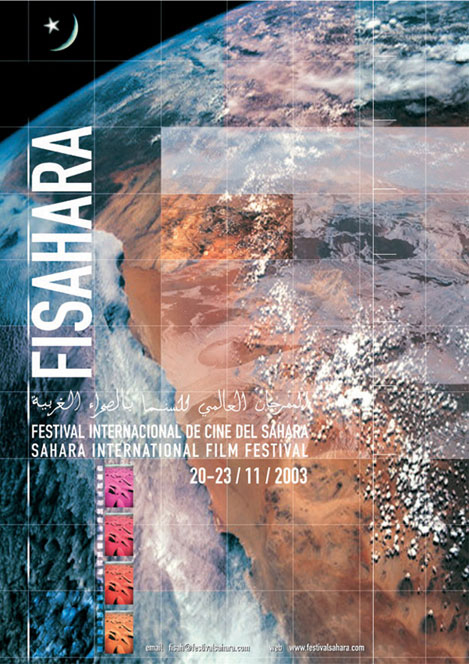

FiSahara 2003 Official Poster

It was the very end of 2002 when Peruvian documentary film director Javier Corcuera landed in the small airport of Tindouf (Algeria), in the heart of the Sahara Desert, for his first visit to the Sahrawi refugee camps, where almost 200 thousand exiles from the Western Sahara have lived since escaping the Moroccan invasion of their homeland in 1975. His visit had been arranged at the invitation of the Polisario Front, the Sahrawi national liberation movement, and Pepe Taboada, one of the founders of the Spanish solidarity movement with Western Sahara and the now-president of the solidarity platform known as CEAS-Sáhara.

Javier, known for making internationally acclaimed films addressing social justice such as The Back of the World, spent an unusual New Years’ Eve sipping tea and eating Sahrawi home cooking inside a traditional tent known as a haima. His hosts took him on a tour of the camps to meet exiled Sahrawis and then made their proposal: could he make his next film about the story of Western Sahara and the struggle of its people? Deeply immersed in a production about the war in Iraq, Javier proposed instead organising a film festival in the refugee camps.

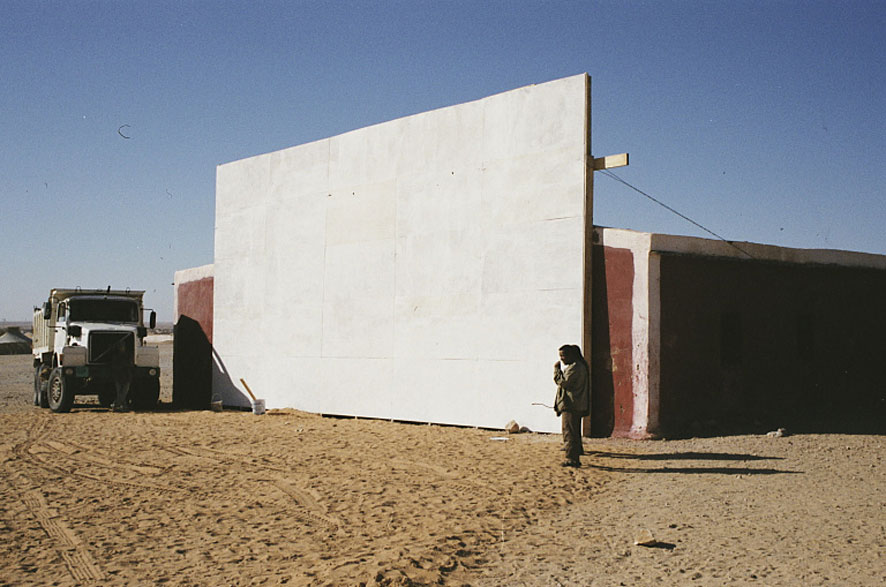

And as tends to happen with proposals that are seemingly impossible to carry out in the middle of a desert with no electricity, running water or other basic infrastructure, the Sahrawi people ran with the idea. Less than a year later, FiSahara’s giant screens emerged from the sand to project films under the stars before large crowds of Sahrawi and international audiences, including dozens of film stars and filmmakers.

The Desert Screen (Iker Amas)

The festival was conceived as a way of introducing film, a new art, to the people of Western Sahara, and just as importantly to raise international awareness about the Sahrawi struggle against the Moroccan occupation of their homeland and the neglect and invisibility that Sahrawis suffer at the hands of the international community.

The films that screened during Fisahara’s first edition were non-competitive, but the festival came up with a unique prize for the festival’s most popular film: a live white camel, the Sahrawi symbol of peace, would be awarded.

And so, on November 20, 2003, the first edition of the Western Sahara International Festival, FiSahara, took off (on the photo above, a screening of Sweet Sixteen on the Desert Screen – Joss Barrat)

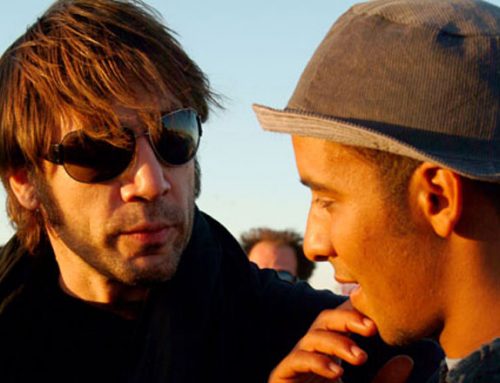

Paul Laverty (Joss Barrat )

“At Madrid airport, a mixture of 250 filmmakers (mostly Spanish), actors, press and solidarity workers loaded up piles of supplies, including 21 full-length feature films that were to form the heart of the festival,” is how Scottish screenwriter Paul Laverty described his experience traveling to the Smara refugee camp in an article published in The Guardian.

Laverty was one of many people from the world of film who traveled to the Sahara Desert for that first edition, and the experience deeply impacted him: “We arrived in pitch dark. There wasn’t a single light to be seen in a settlement with over 40,000 souls. By torch we were hustled through into an open-air adobe enclosure and the chaos began. You might think it would be a simple task to divide 250 into groups of five – and then for each group in turn to be assigned to a Saharawi family. No… but it didn’t matter. It felt biblical: bleating goats, a scramble of kids, a circle of women in bright veils barking orders and by the gate, a tall, elegant Bedouin figure towering above us, watching in silence. A young boy of nine held me firmly by the hand as he led us (one Scott, one Englishman, one Basque, two Peruvians) through the darkness, skilfully avoiding deep holes dug to extract sand for adobe bricks.”

In an article published in The Times during the second edition of the festival, journalist Samuel Loewenberg writes that “of the 185 thousand refugees, almost one half were born in the camps.” In a chapter dedicated to FiSahara in Setting up a Human Rights Film Festival, a handbook published by the Human Rights Film Network, FiSahara’s current Executive Director María Carrión writes: “The first edition, held in November of 2003, is remembered by all who experienced it as nothing short of a miracle—a truly magical event that at times came close to disaster.

Dozens of Sahrawi electricians, engineers, artists and local leaders in the camps prepared the event on the ground. In Spain, people volunteered to travel to the festival as projectionists, sound technicians, producers and workshop facilitators, many loaning their own equipment… local planners had erected a giant movie screen on the side of a truck, conditioned small adobe buildings and pitched desert tents for festival activities. Families opened their haimas and welcomed perfect strangers into their homes.

Children’s screening (Andrea Comas)

Logistically, the festival constantly seemed on the verge of collapse. Electrical blackouts darkened screens and silenced microphones. Equipment overheated or broke down. There were no cell phones or walkie-talkies for team members to communicate, leading to mad races under the scorching sun. Most of the Spanish team became ill; at one point all the projectionists were out sick on the same day.

Still, it worked. When FiSahara’s outdoor Desert Screen first lit up, the vast majority of the audience sitting under the stars had never seen a movie before. Before them appeared Winged Migration, a spectacular French documentary that lifted the audience to the heights of migrating birds flying over oceans, forests and deserts.”

Participants of the round tables (Antonio Rojas)

The need for an event like FiSahara was obvious. And this adventure had only just begun, because the Sahrawi people were hungry for this new art, film and filmmaking, and desperately needed the kind of media attention that was denied to them for the rest of the year.