“My passion for film was born at FiSahara film festival. As I sat before its big screen, I felt my wings spreading and my body flying out into the world. For the first time, I understood the enormous power of film… I saw how film was able to make stories bigger than life, how it moved passions and changed lives. I took a film class at one of the festival’s workshops and knew then I had found my destiny.”

These are the words of Brahim Chagaf, a young Sahrawi filmmaker recalling how his love for film was ignited.

Brahim Chagaf at FiSahara in 2016. (Alberto Almayer)

“I imagined making Sahrawi stories that were bigger than life as well, and projecting them on that giant screen and other screens all over the world so that we would no longer be a forgotten people. Each year, my friends and I would head for FiSahara and enroll in the workshops, and eventually we set out to convince the festival that we needed a film school in the camps so we could study all year”.

As our previous article mentioned, FiSahara had a firm commitment from its first edition to teach filmmaking to the Sahrawi community. The aim was for Sahrawis to to tell their own stories and reclaim their struggle through film.

FiSahara’s workshops were in high demand among Sahrawi youth. One group of aspiring Sahrawi filmmakers attended every edition in order to pursue cinematic studies—a novel opportunity for the community. Along with the festival itself, the workshops were part of an initiative known as “Film for the Sahrawi People”.

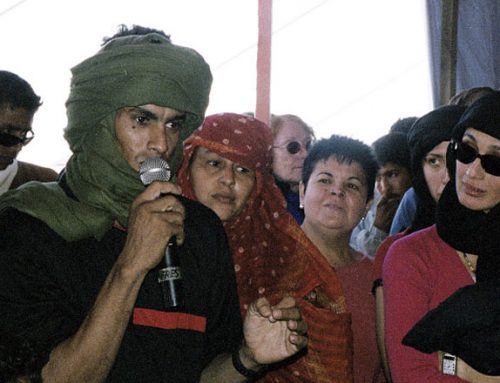

Culture Minister Khadidja Hamdi supervises the work at the start of construction.

But an annual workshop did not provide enough training, and young Sahrawis suggested a program that would allow them to study year-round, giving birth to a project to build the very first film school of Western Sahara. It was an ambitious goal: a permanent school that would offer a two-year program as well as the possibility to house students from the different camps. In 2009, during the 11th edition of FiSahara, the festival announced it would lay the first brick of its film school campus and obtained funding from the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID), as well as from donations from visiting filmmakers and artists.

The school would be built in the 27 February refugee camp, now known as Bojador, where other schools had been created.

Khadidja Hamdi, then Minister of Culture for the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), described FiSahara as a “window of solidarity”, stating that cinema is an “essential tool for the development of every country, as it raises awareness and shapes humankind”.

One year after the announcement, as FiSahara 2010 drew to its conclusion, the Abidin Kaid Saleh Film School opened its doors. It was named after the first Sahrawi war correspondent, Abidin Kaid Saleh (1954-2003), who reported on the long war against Morocco (1975-1991) and is considered to be one of Western Sahara’s best wartime photojournalists.

The school’s Academic Director, Spanish filmmaker Roberto Lázaro with Spanish actress Victoria Abril (D.Bollero)

Along with Sahrawis from different refugee camps, the project brought together SADR authorities, the school’s new director Omar Ahmed — himself a war correspondent — the school’s Academic Director, Spanish filmmaker Roberto Lázaro, and film industry celebrities, many of whom had contributed funding. With still much work to be done to fully outfit the facilities, courses were set to begin that September. There were 15 students in total, from different refugee camps, many of who would board at the school.

The student body, with ages ranging from 18 and 21 years old, came from different experiences. Some had worked with Sahrawi television (RASD-TV) and had basic audiovisual notions, while others had participated in FiSahara workshops. Some applied without prior film experience.

The program was ambitious: it offered around one thousand training hours spread over three trimesters—10 modules of three weeks each. Upon completion, students were awarded the degree of Technical Specialist in Film, Video and Television. Instructors at first were mostly made up of volunteer filmmakers from Spain as well as a few from Latin America, reflecting the nature of FiSahara’s initial workshops.

The first graduating class of Sahrawi filmmakers from the Abidin Kaid Saleh Film School. (José Medina)

FiSahara’s 2012 edition celebrated with pride the first graduating class of Sahrawi filmmakers from the Abidin Kaid Saleh Film School. Even though Sahrawi-made short films had previously been made and screened during the festival’s workshops, this was the first year that the festival dedicated an entire section to Sahrawi-produced works.

And the quality of the work continued to increase. In 2013 the students won FiSahara’s second prize for best film for Divided Homeland, he first-ever feature entirely made by a Sahrawi film team. It tells the story of a young Sahrawi man from the Morocco-occupied Western Sahara who crosses the separation wall and arrives in the refugee camps, a place where he is no longer followed, abused or jailed; a place where his identity is treasured and reaffirmed, not denied. It is also a love story.

FiSahara had screened other feature films on Western Sahara, but this was the first time that Sahrawi audiences were able to watch one told from their own perspective. Brahim Chagaf, one of the film’s directors and its main actor, said about the film’s debut at FiSahara: “As Divided Homeland played on FiSahara’s Desert Screen to a huge crowd of Sahrawi families and international visitors I looked around and saw that everyone around me was crying. That’s the moment I would pinpoint when Sahrawi cinematography was born“.

Sahrawi filmmakers have come into their own. In 2016, Brahim Chagaf, Hayetna Mohamed Deidi, Ahmed Bachir and Hayat Rguibi (who is from the Morocco-occupied Western Sahara) participated in the youth jury at the San Sebastian Human Rights Film Festival as part of the San Sebastian 2016 European Capital of Cultural (SS2016).

Brahim Chagaf collects the first prize from FiSahara (Alberto Almayer)

By 2016 a Sahrawi co-production was awarded the festival’s first prize, the White Camel. Leyuad: A Trip to the Verses Well is a poetic road movie co-directed by Brahim Chagaf, Gonzalo Moure and Inés G. Aparicio and filmed in the liberated Western Sahara that digs deep into the roots of Sahrawi poetry and identity.

Today, the Abidin Kaid Saleh Film School has become a fundamental pillar for Sahrawi efforts to document, preserve and transmit Western Sahara’s rich history and culture and to raise global awareness about the conflict and its tragic consequences. Films made by students travel to festivals such as the African Film Festival – Lausanne (Switzerland), where Brahim Chagaf and Ahmed Omar stepped into spotlight with their films Leyuad and Retrato (Portrait).

Lázaro shows the school to several Spanish actors (D.Bollero)

Thanks to scholarships from the San Antonio de los Baños International School of Film and Television, the Madrid Film Institute, the Chaminade student residence (Madrid) and NomadsHRC, the Abidin Kaid Saleh Film School now has a group of year-round Sahrawi instructors. They are now a mainstay of the first film school in Western Sahara.

“We were 18 young women and men stepping onto unknown territory, all with big dreams and all convinced that film would help us liberate our people. During the two years I spent as a student at the modest little school, where we would sometimes make do all day with a plate of rice and beans and no electricity or water, we learned that filmmaking was painstaking; that it took infinite patience and hard work, but that the results could be magical. We learned that it is possible to make films with just sand and rocks and an old camera as long as we knew how to tell our stories. We, the children of women who built the refugee camps with pails of sand and their bare hands, felt we could do anything”.

This, too, was written by Brahim Chagaf, who now teaches in the same school that made him into a filmmaker.