The COVID-19 pandemic and the return to war in Western Sahara have left the Sahrawi cultural community in the refugee camps with very little access and resources for culture and entertainment. With all international events canceled or indefinitely postponed, including FiSahara; the film school closed for the academic year and scarce funding for arts and culture, there were few opportunities for Sahrawi refugees to enjoy communal events around music, poetry, theater and film.

Thanks to a COVID relief grant from Prince Claus Fund, which in the past has supported both FiSahara and the Abidin Kaid Saleh Audiovisual School, the camps came alive once again with cultural activities.

‘Sólo son Peces’ screening. (Wita Alien)

The funding was quickly deployed to the areas most in need and was stretched to cover three different cultural disciplines. Middle and high schools put on plays written by students, women’s musical groups re-convened to compose and perform after almost a year of silenced microphones, and community libraries became improvised movie theaters where screenings were followed by animated debates. Youth and children were at the center of these activities — both as organizers and as participants.

The short film by Al Borde Films captured the full attention of the audience . (Wita Alien)

Schools from four refugee camps participated in a theater production contest that took place in February. With the help of their teachers, students wrote, produced and performed plays telling stories about their lives, about the war and about their hopes for the future. Music was also infused with new energy through a competition between women’s musical groups, each of which represented a different refugee camp. The songs they wrote and performed narrated the singular moment that Sahrawis face, in the midst of a war and a pandemic, adding to the rich Sahrawi oral repertoire of stories that can be passed on to future generations.

Recording of the interviews with women who work in the wilayas by the children. (Wita Alien)

“Many of the kids have a family member on the warfront“, explained Abidin Salec, one of the members of the team who was also part of the Prince Claus-funded Lmzun project. “This project has given Sahrawi kids the opportunity to express both their anxieties about the war and their hopes that peace will soon come to Western Sahara, and that they will finally be able to leave their lives as refugees and go home. Through the arts, they have also opened a window into the situation on the other side of the separation wall, where Sahrawis peacefully resist the occupation“.

Laughter, curiosity and amazement during the interviews. (Wita Alien)

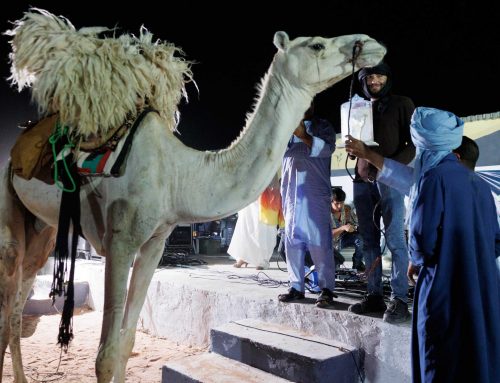

FiSahara Screenings on International Women’s Day

Cinema capped off the activities supported by this grant in a collaboration between FiSahara, NomadsHRC and the Bubisher community libraries — a network of brick-and-mortar and mobile libraries located throughout the camps, mostly run by young women, that foment reading among children and youth.

(Abidin Salec)

On March 8th, International Women’s Day, the libraries turned into cinemas and screened the acclaimed film They are just Fish (Solo son peces), a documentary by two women filmmakers from Spain, Paula Iglesias and Ana Serna (Al Borde Films), in collaboration with the EFA Abidin Kaid Saleh film school, that tells the story of how three Sahrawi women built and ran a fish farm in the refugee camps, in the middle of the Sahara Desert. The film was recently nominated for best documentary short at the 2021 Goya film awards, the Spanish equivalent of the Oscars.

They are just Fish is a story of resilience and inventiveness; of three women overcoming seemingly impossible obstacles — such as trying to keep a large amount of fish alive in the midst of a barren desert with little access to water and soaring temperatures of up to 50 degrees Celsius in the summer. It is also full of symbolism and irony: the women breed tilapia, a species originally from the Nile that they call a “refugee fish far from its homeland”, much like their own experience as refugees exiled from their land, the Western Sahara.

Children were also protagonists in this day of women’s empowerment. (Abidin Salec)

“The kids were amazed to see how these women were able to breed fish in the middle of the desert ” said Gajmula, a librarian at the Bubisher library in the Ausserd refugee camp. “And while I was marveled at their feat, I also kept thinking: How can it be that back in our occupied homeland of Western Sahara our ocean is so rich with fish, but yet we are forced to breed them in a refugee camp thousands of kilometers away? How can the world allow Morocco to benefit from plundering our rich waters while forcing us to live on humanitarian aid? This is not justice!”

After the screenings the libraries held a series of discussions both about the fish farm — most people had no idea about its existence — and more broadly, about Sahrawi women’s role in society and the enormous responsibilities that they bear: on the one hand in the home and community, and on the other through their professions. Several professional women spoke with the kids about their work, and how difficult it was to balance work and family life.

Distribution of informative material among the attendees. (Wita Alien)

On that day, there were also a series of discussions in the libraries with gynecologists and midwives for women about breast cancer prevention and detection, as well as other issues that addressed the medical needs and issues affecting Sahrawi women. One discussion by a woman psychologist centered on how the difficulty of identifying cases autism in the Sahrawi community, and addressed more broadly mental health among children.

For the rest of the week, the libraries are working on two short films. One features conversations between children and youth and women who are working outside the home: a doctor, a police officer, a water distributor, a psychologist, a painter, a midwife, a nurse, a teacher, a women’s rights activist, the director of center for persons with disabilities, a librarian, a cook, a journalist and a veterinarian.

Colloquium with one of the experts. (Wita Alien)

The second film is called Innovators, and is inspired on the film They are Just Fish, and the premise that necessity is the mother of invention. If three Sahrawi women refugees can successfully operate a fish farm in the middle of the desert, what other innovative ideas can children and youth come up with? Through the use of mobile phones, participants are filmed drawing and describing their inventions.

“After months of cultural drought, we were thirsty for the creative process to begin once again, and this grant has watered our very dry desert. We are truly thankful to all our supporters for this opportunity“, said Abidin Salec.